Dr. Oscar Livingstone Simpson, contemporary of my parents, practiced medicine in East Tennessee, mostly Maryville, from the 1950’s to the 1990’s, and he wrote a book about it. The name of the book is My Dadaw Used To Be A Doctor, 2004, Stinnett Printing, Maryville, TN. Unfortunately, it is out of print and generally unavailable, and when I called Dr. Simpson in the fall of 2009 to ask about it, he said he had done the book for his children and grandchildren and had no plans for a reprinting.

I had read my mother’s copy of the book two or three years ago before all the health care bill negotiation got under way and kept thinking that the doctor’s recollections included many great stories that illustrate one way that the US health care system has regressed rather than progressed over the past fifty years. We had circulated the book around among family members, and it took a little time to find it and read it again but doing so affirmed my thoughts. The major loss has been corruption of the patient-doctor relationship through injection of private and government insurers as the true bill-paying customers of the doctors.

In the fifties, there was much less specialization than today, and doctors divided their time between hospital rounds, office hours, house calls, baby deliveries, and even surgery. It was a brutal schedule they followed, but it paid pretty well and I think most doctors saw it as an enjoyable life of service to their fellow humans. That is certainly the tone of Dr. Simpson’s memoir. Doctors set their own rates for services provided and collected directly from those they served.

Dr. Simpson relates the story of a lady who came to his office in 1955 shortly after he had raised rates for an office visit from $2 to $3. (That’s a 50% increase!)

“After I had completed checking her she complained, ‘Doctor, I understand that you’ve raised your fee from two dollars to three, but you’re not worth but two dollars!’ She then plopped down her two dollars and left in a huff.”

He also tells of a farmer who appeared to be very poor and for whom he voluntarily cut his fee in half.

“To my dismay he pulled out a wad of bills that would choke a horse, peeled off a fifty from the roll, and said, ‘Is that all, Doc?’ So you can’t always tell what a person’s financial status is by the way he looks.”

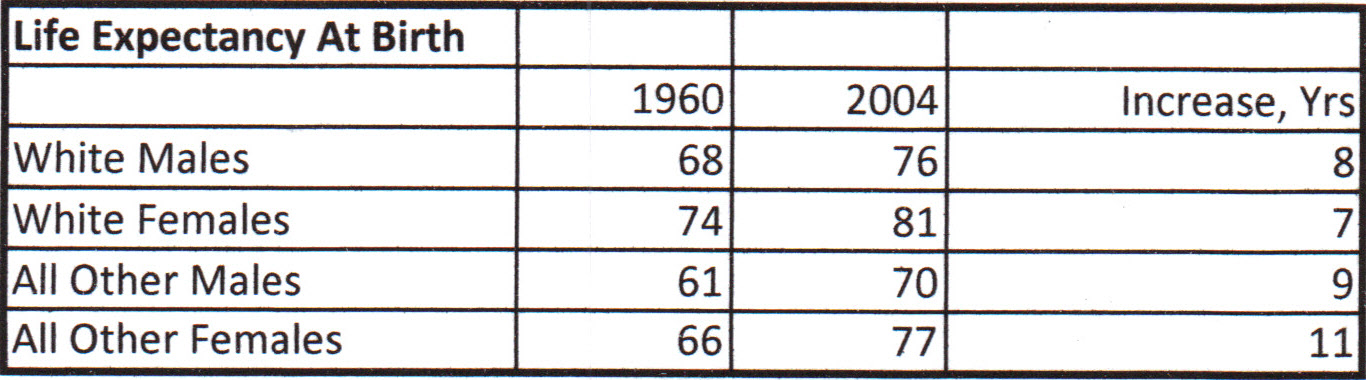

I know what you are thinking. That was the dark ages, everybody died young, and we have come a long way since then. Well, life expectancy is better. I found some data.

Life expectancy has increased because of improved nutrition, inoculations, antibiotics, and diagnostic, pharmaceutical, and surgical technology and not because the patient – doctor relationship has been corrupted by hundreds of thousands of insurance company and government employees being imposed on the system and taking a large share of the health care dollar.

(The table above does raise an interesting question about Social Security. What if Social Security law had been written so that benefits begin at average life expectancy minus 3 years for males and average life expectancy minus 9 years for females? That was the immediate effect of the law as written in 1965.)

I wish everybody could read Dr. Simpson’s book. It brought more spontaneous laughter than anything else I have read in a long time. Here’s a sample:

“One month I delivered thirty babies. Usually I didn’t see the father of the baby until I went to congratulate him after I delivered the baby. One day I extended my hand to a young mountain boy who had a three-day beard and manure on his boots…When I said, ‘Your wife just delivered a fine, healthy, eight-pound baby boy,’ he replied, ‘Well, what’s its name?’”

Thank you, Dr. Simpson, for this memoir.